Can you do everything?

What did you get done today that you wanted to do?

Exceptionally productive people understand a simple truth:

being more productive doesn’t mean getting more done. It means getting more of the right things done.

Willpower Doesn’t Work. Here’s the Key to Being More Productive According to Neuroscience.

We have to outsmart the part of our brain that wants us to fail.

I used to believe that being more productive meant getting more done. That my personal productivity was defined by the sheer volume of tasks that I managed to take down each day.

And then one day, tired, exhausted, in a fit of rage that included heavy cursing and the belligerent kicking of stuffed animals (I happened to be in my young niece’s bedroom at the time) I experienced somewhat of an epiphany.

I shouldn’t define productivity by the total volume of tasks I manage to accomplish. After all, do I really care, at the end of the day, how many activities I get to cross off my list of to-dos?

What I should care about, I reasoned to myself, is what those activities promise to earn me. The benefits. The payoffs. The things I really cared about: fulfillment, money, health, status, impact, deeper relationships, etc.

And so right then and there, I decided to begin measuring my productivity using another metric. A metric I call return on effort.

In other words, instead of blindly executing one task after another as it appeared in my inbox, I would regularly ask myself a crucial question: what are the total rewards I expect in return for the total time I’ll spend to get them?

When I came to measure productivity in this way, it became immediately apparent that not all activities were created equal.

Indeed, there were two kinds of activities which, when I considered return on effort, differed considerably: maintenance and growth.

Maintenance vs Growth

Maintenance activities are effectively short-term obligations.

They are the “musts” in our life: consultants must consult, surgeons must perform surgery, managers must manage as well as occasionally conduct performance reviews.

Each one these professionals, moreover, must pay their insurance bills, file their taxes, and respond to emergencies that threaten to burn the house down, either literally or metaphorically.

To be sure, maintenance activities are necessary to perform. We’ve got to do them. Ignore them and you’ll eventually end up unemployed. Homeless. In the clink with the mob still trying to get to you on the inside.

However, for those looking for more than just survival, or even mediocre success, maintenance activities are nowhere near sufficient. Because what most people fail to realize is that these short-term obligations deliver relatively meager return on effort.

Maintenance activities, just like they sound, don’t do much more than maintain the status quo, preventing us from losing what we already have.

But then there are growth activities.

Growth activities drive our most important long-term goals. They take us beyond the status quo. “Could” rather than “musts”, these activities, as a result, deliver comparatively high return on effort.

Often strikingly so.

A consultant could spend a couple of hours each day for six months writing and publishing a book — I know one who did and in just a few short years, began earning 7x his salary.

A surgeon could deliver eight speeches a year at high profile conferences and soon find herself a nationally recognized authority with regular appearances in national media.

A manager could carve out time every single morning to read books on behavioral economics, and cognitive psychology, and in eight months become the best damn decision maker in the building.

And so it’s no surprise then, that when you look at the schedules of the world’s most productive people — the Elon Musks, the Oprah Winfreys, the Kevin Harts — what you invariably find is this: a disproportionately high number of growth activities.

Indeed, exceptionally productive people understand a simple truth: being more productive doesn’t mean getting more done. It means getting more of the right things done.

Unfortunately, most professionals, even relatively effective ones, manage to execute a depressingly small number of growth activities.

Not by choice. They try to take on more. However, a pernicious tendency stands in the way: procrastination.

They tell themselves that tomorrow they’ll start their online project management course, meditation practice, investment portfolio.

But when tomorrow comes, they find themselves unwittingly putting it off until the next day, and the then the next day, and then the next day. Until eventually they abandon the growth activity altogether.

That is until months later when the cycle repeats.

In the face of this procrastination, professionals tend to blame themselves. They uncharitably berate themselves for lacking the drive, the resolve, the inner strength.

But they shouldn’t.

Recent discoveries in neuroscience have revealed the real reason we fail. The true, nefarious culprit. A primitive system in our brain that doesn’t quite share our priorities.

But in order to illustrate exactly what that system is and what we can do about it, I need to first tell you a story.

The Real Reason We Procrastinate Growth Activities

I want you to imagine the driver of a car on his way home from work, cruising down a long and narrow road.

This driver, whom we’ll simply refer to as the Driver, has just recently decided to take on what he believes to be his most important growth activity: writing a book.

He’s motivated. He’s determined.

And now coming up on his right in about one mile is the library where he’s promised himself he’ll get started.

Now just as he’s about to make his right turn, he happens to see in the distance, that the local movie theater is screening the new Star Wars movie.

The Driver, committed to his growth activity, tries to ignore the distraction. He looks away. He bites his hands. He whistles loudly the tune to Stronger by Kelly Clarkson.

But it’s no use. He’s struck by a powerfully irresistible feeling that practically bars his hands from turning the steering wheel right.

After the movie, on his way home, 3-D glasses and half empty popcorn bucket on the seat next to him, he curses himself for making such a terrible choice.

The next day the Driver vows to do better. Today’s the day, he tells himself.

But this time, as he nears the right turn, out of nowhere, a thought hits him like a bolt of lightning: I can’t work on my book today, I have that urgent client report I need to write. So the Driver speeds past the library, races home, and plunges into his client work instead. The next morning, he wakes up and wonders, “What the hell was I thinking?”

For the next few days, the Driver continues to try to make the right turn, but fails every single time.

Dejected and confused, unable to understand why he keeps failing to do the very thing that he so desperately knows he should do, the Driver gives up. He throws in the towel.

At this point, the Driver needs help.

That’s where we come in to the story. You and I, dear reader, are his advisors. And our first task, in order to help the Driver overcome his procrastination, is to figure out why. What exactly is the root cause of the driver’s irrational behavior?

If we look again closely at the picture of the Driver sitting inside his car, we’ll quickly learn his persistent failures are no accident.

They’re sabotage.

Sitting beside the Driver, unbeknownst to him, is a passenger. An invisible bloke who, every time the driver tries to make his right turn, makes sure he doesn’t.

To the Driver, his inability to make the right turn is a bug. To the Passenger, it’s a feature.

If we want to help the Driver consistently make his right turn, arrive at library, and perform his growth activity, we have to first answer two obvious questions: Who is the Passenger and what in God’s name does he want?

Who is the Passenger?

By now you probably realize that the Driver and Passenger are a metaphor for the profoundly conflicted nature of the human mind.

The Driver represents the rational part of our brain. The more recently evolved prefrontal cortex. This is where we reason, make decisions, and plan for the future.

The Passenger, on the other hand, represents what is often thought of as the emotional part of our brain, the more primitive limbic system. One of the limbic system’s most important responsibilities is to respond rapidly to potential threats in our environment.

It’s clear from our story that the Passenger sees growth activities as one of these threats. But why? Why would part of our brain want us to avoid such high return on effort activities that, as we’ve learned, most help us thrive?

To make sense of this puzzle, we need to go back hundreds of thousands of years to a time when our singular priority wasn’t to thrive. It was to survive.

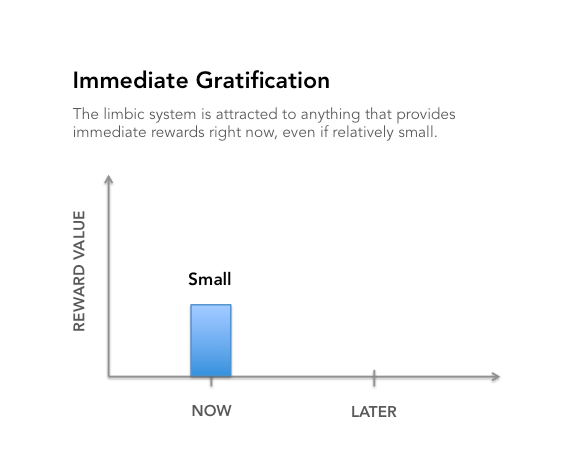

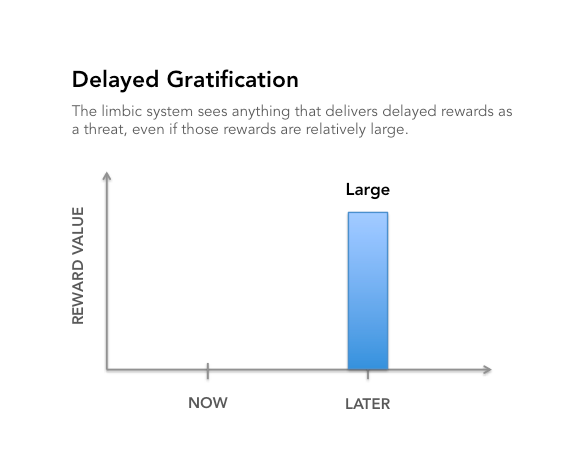

In an incredibly dangerous primitive world, early man couldn’t afford to spend his precious time and energy on activities that delivered delayed rewards, such as saving food for a rainy day or practicing proper running technique. By the time the payoff for these activities arrived, he might have already been devoured by a giant hyena.

Instead, he was better off spending his limited time and energy on activities that promised to deliver immediate rewards. Presently available ones like food or sex.

And so, evolutionary psychologists theorize, individuals who had Passengers with a strong preference for immediate rewards, or what we might commonly refer to as immediate gratification, were more likely to survive and pass on copies of their genes.

Today, of course, we are living in a radically different environment. But because evolution hasn’t quite caught up yet, we are still endowed with Passengers that strongly favor immediate gratification, and conversely, disfavor delayed gratification.

What a terrible, terrible, shame. Because growth activities, entail none other than delayed gratification. Whether it’s studying for the bar, practicing free throws, or reading long educational articles such as this one, the one thing these activities have in common is they require substantial effort now, for a greater payoff later.

Nonetheless, the Passenger, still attuned to our ancestral environment, sees growth activities as a threat to survival. Consequently, he does whatever it takes to make sure the Driver avoids them.

So now we know who the Passenger is, along with why he is so intent on sabotaging the Driver’s attempts to execute growth activities. But in order to devise a solution, we need to understand the Passenger’s modus operandi. How exactly does he compel the Driver to procrastinate?

As you’re about to learn, the Passenger has a remote control. A rather invasive one. It allows him to access and manipulate the Driver’s mind. His thoughts. His feelings.

You see, the Passenger is no ordinary passenger.

He’s a professional hacker.

How the Passenger Hacks the Driver

To get a better sense of how exactly the Passenger manipulates the Driver, let’s take a play-by-play look at the hacking in action.

When the Driver first forms his intention to go to the library, the right turn is far enough down the road, that to the Passenger — who is primarily sensitive to concrete sensory information — it remains a harmless, abstract idea.

However, as the right turn approaches, the sights and sounds associated with the library start to become salient. And The Passenger sits up in his seat.

It’s at this point the Passenger presses the fear response button on his remote control. This sends signals to the Driver’s hypothalamus, which in turn activates the pituitary gland, resulting in the secretion of fight-or-flight hormones such as cortisol and norepinephrine into the bloodstream. These chemicals cause the Driver to experience an elevated heart rate, faster breathing, increased blood pressure, and greater overall brain arousal.

But the most consequential effect of these physiological responses, perhaps, is how profoundly it alters his perception. It’s like the Driver has unknowingly put on a special set of “fear goggles”, goggles that cause him to now see the world through the eyes of the Passenger. That is to say, immediately rewarding activities appear more vivid, compelling, while delayed reward activities appear dull and uninspiring.

The consequences of this altered perception is a dramatic change in feelings I call: The 180. While just an hour prior, the Driver felt the right turn to go to the library was vitally important, now he feels it to be largely a waste of time.

At the same time, a previously mild interest in seeing Star Wars, now feels like an obsession. Similarly, moderately important client work suddenly feels like it deserves immediate, unwavering attention.

As a result of these sudden changes of hearts, the Driver puts off the now aversive growth activity in favor of the more immediately rewarding maintenance activities.

He procrastinates.

So now that we understand the mechanism by which the Passenger, that backstabbing, roguish, rapscallion, prevents the Driver from making the right turn, the question is: what can the Driver do about it?

The Unfortunate Unreliability of Willpower

At this point, you might suspect the Driver’s best hope of overcoming the 180 is willpower. Willpower is famously the process by which we consciously fight back against the Passenger, attempting to regulate the emotional flooding that he sets in motion. But we should hesitate to advise the driver to rely on willpower for two reasons.

First, as much as the Driver may want to initiate the right turn, willpower just doesn’t stand a match for the powerful surge of emotions triggered by the fear response.

We’ve all had the experience, especially after a long hard day, of trying our damnedest to head down to the basement to practice our Subcontrabass Flute. Only to fail miserably.

We want to, but we just can’t — the aversive feelings are too strong to overcome. Granted, willpower might help the Driver win a few of his battles, but over the long haul, trust me, he’ll lose the war.

But there’s another reason, a more important one I argue, that willpower is not a reliable way for the Driver to overcome the 180: the Passenger often manipulates the Driver into not even wanting to initiate the right turn.

Indeed, not only does the Passenger’s fear response alter the Driver’s perception, through mechanisms neuroscientists still don’t completely understand, it often hijacks his reasoning faculties as well. When this happens, the Driver doesn’t resist the 180. He rationalizes it.

Ask the Driver why he’s not going to the library and he’ll rattle off a list of reasons why it’s not so important after all. Why it rightfully deserves to wait.

What’s worse, he believes every one of his own lies. As a result, the Driver doesn’t even think to recruit willpower until after the episode is long over and he’s finally come to his senses. Of course, by then it’s too late.

So willpower won’t do the trick. And any solution that will, has to contend with this sobering fact: once the Passenger hacks the Driver, he may not be of enough sound mind to want to even initiate the right turn, and therefore have any motivation to use it.

But what if there was solution that made it so that the Driver didn’t have to want to initiate the right turn? What if the Driver didn’t have to initiate the right turn at all?

Stay with me for a second.

What if the Driver could, in advance of the hack, while he is still of sound mind, automate the right turn, the same way we can automate our alarm clock to go off at a certain time. That way when the Driver becomes inevitably brainwashed, the right turn would still go on automatically. Sound impossible?

It would be, if not for a shocking detail of which the Driver is currently unaware.

The car he’s been riding around in is no ordinary car: it’s a programmable self-driving car.

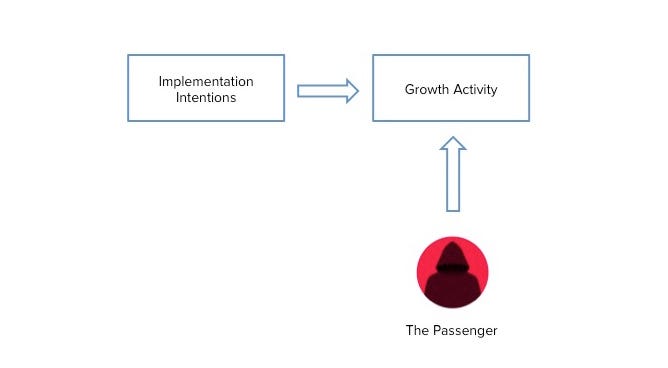

The Astonishing Effectiveness of Implementation Intentions

If the Driver and Passenger represent the prefrontal cortex and limbic system respectively, the self-driving car represents a system of the human brain, that we have just in recent decades learned is effectively programmable: procedural memory.

It’s hard to convey how extraordinary this discovery is. Granted, we’ve long known that procedural memory is the domain of lots of automatic behaviors, namely habits. Procedural memory is what allows us to brush our teeth every morning, turn off the lights when we leave the room, or throw our computer against the wall when we get to a website with unstoppable auto-play video ads.

But normally, these kinds of actions get stored in our procedural memory as a result of a slow learning process. Only after many repeated experiences, over a period of weeks, or even months, does the action become automatic.

It’s only recently that psychologists have learned a way to install these habits in a matter of seconds. Amazingly, in just one quick sitting, we can effectively “program” them into our procedural memory. But how exactly?

The answer is with a technique known as implementation intentions. Don’t worry. While the technical name makes them sound intimidating, their underlying concept is quite simple: we just decide what specific action we want to take as well as specifically when and where we plan to perform it.

Researchers have found the best results when subjects formulate these decisions using simple IF-THEN statements. Where THEN precedes the activity we wish to perform, and IF precedes the situational cue that specifies when and where we should perform it. For instance: “IF it’s after lunch THEN I’ll work on my presentation.”

Indeed implementation intentions are so simple, that upon hearing about them people inevitably ask: how is that any different than what I normally do?

When we take on new activities, we often stop short of forming implementation intentions, and instead create goal intentions — which take the even simpler form of “I intend to do X”.

When we form a goal intention, while we may indeed specify the action we want to perform, we don’t specify the cue that tells us when we should perform it. For an illustration, just think of the vast majority of to-do lists you see scattered across homes and offices all over the world. All actions, but no cues.

That, it turns out, proves to be a tremendous missed opportunity. Because when we specify both the action and the cue, the two become linked together in our minds. The resulting linked cue-action program is then stored inside procedural memory.

The result is what the social psychologist Peter Gollwitzer calls an instant-habit.

Now, here’s the magic. Just like habits don’t need to be consciously initiated, neither, now, thanks to our implementation intentions, does our growth activity. When the cue arrives, the growth activity is triggered automatically.

For example, had we previously specified we would begin working on our presentation immediately after lunch, as soon as we finish our sandwich, we might find ourselves walking to our office to begin our work, without even consciously realizing it, and even if we didn’t particularly feel like it.

It’s as if our own personal autopilot has been activated.

Granted, in the real world, implementation intentions don’t guarantee success but they dramatically increase the chances. Indeed, over one hundred studies show that implementation intentions can double, sometimes even triple the chances people successfully carry out all different kinds of aversive activities, from exercise, to writing essays, to creating resumes.

Moreover, I’ve personally witnessed how effective this simple exercise can be. I’ve seen people through the daily use of implementation intentions, quickly go from perpetual procrastinators to productivity phenoms. Implementation intentions are truly the linchpin exercise for exceptional productivity.

Let’s inform the Driver, shall we?

The Driver, now armed with our advice, each day at 5pm, pulls over to the side of the road. A mile out from the library, he reaches for the interface on the dashboard that allows him to program his self-driving car.

He instructs the car, that when it reaches the street the library resides on — Main Street — to turn right. (IF Main Street THEN turn right). When he’s finished, the Driver begins heading towards the library.

As the right turn approaches, the Passenger executes his fear response like usual and the Driver finds himself in the midst of the 180. But just as the Driver, fear goggles firmly in place, is about to speed past the right turn, something extraordinary happens.

The wheel begins, by itself, turning to the right. Soon thereafter the Driver finds himself at the library, finally beginning his book.

Eureka! The Driver has beaten the Passenger for good.

Or has he?

About one week later, just as we begin to congratulate ourselves for helping our beloved Driver overcome his procrastination, he comes back to us with some unfortunate news.

While in the first few days, the implementation intentions worked like a charm, he tells us, he soon found himself failing to perform them consistently. Days later he’s embarrassed to admit he gave them up altogether.

By now, we can already guess why: sabotage.

Did you think the Passenger, faced with an existential threat, would go so quietly into the night?

That two-timing hellion has one more trick up his sleeve.

And it threatens everything.

The Passenger Strikes Back

Let’s review, for a moment, why the Passenger hates growth activities so much in the first place: he sees any activity that involves delayed gratification as a threat. Which was, of course, our reason for telling the Driver to perform implementation intentions. To ensure his growth activities get initiated, even as the Passenger tries to thwart him.

But when dispensing this advice we, unfortunately, overlooked an important fact: implementation intentions are also an exercise in delayed gratification. Sure, they are relatively brief, but still, they require effort. Furthermore, the payoff for that effort doesn’t come until later. Therefore, it’s inevitable: the Passenger will sabotage the Driver’s attempts to initiate his implementation intentions too.

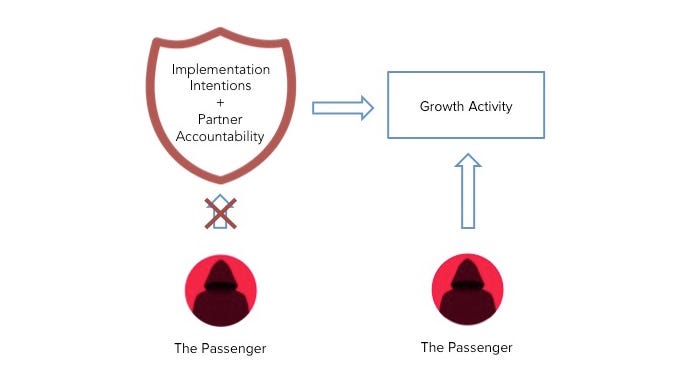

If we want to beat the Passenger once and for all, we have to find a way to deter him from sabotaging the Driver’s implementation intentions, despite them being a delayed gratification activity.

Furthermore, and this is crucial, whatever solution we find needs to be itself un-sabotagable. But does something like this exist?

It does. Remember that above all, the Passenger wants to feel as good as it can right now. That’s why he sabotages activities that requires effort or cause immediate pain. But the Passenger, it turns out, won’t sabotage that activity, if he sees that not performing that activity will lead to even more immediate pain.

So what, then, is something the Driver can do to make not performing implementation intentions immensely painful?

The answer: setup a regular appointment to do them with a partner.

The Grit Protocol

When we setup an appointment to perform any activity with someone else we change the very nature of that activity. We make not showing up at the agreed upon time decidedly painful.

The reason why is not difficult to understand. Throughout our long history, human beings have needed to make sure we keep our commitments with others, or risk being kicked out of the tribe — a likely death sentence for our earliest ancestors. So in order to motivate us to do just that, we evolved to feel social pain when we break our commitments with others.

What’s more, while human beings, no doubt, hate breaking all commitments, there are very few things, for most, that are worse than the social embarrassment we face when we miss an appointment.

We’ve all had the experience of being severely late to a meeting with someone — a boss, a personal trainer, our child’s teacher — and running full tilt to avoid the intolerable pain of missing it, as we imagine the other person with a stern face staring repeatedly at their watch, resentful of their time being wasted.

Therefore, what if the Driver set up a daily meeting with a coach or accountability partner to perform implementation intentions together? It would instantly make not showing up to that meeting quite painful.

Thus, even though implementation intentions are a delayed gratification activity, the Passenger would be far less likely to sabotage them.

Moreover, once these daily appointments were established, they themselves would be un-sabotagable. Because while the Passenger has powerful influence over the Driver’s brain, he has none whatsoever over the brain of his partner. Therefore, no matter how many times the Passenger presses the Fear Response button on his remote control, he has no power to stop the Driver’s partner from showing up and enforcing the accountability.

I call this system of daily meetings The Grit Protocol, or TGP for short. And it is the most effective way I know of to ensure we consistently perform implementation intentions, and consequently, growth activities.

In short, The Grit Protocol is the Passenger’s worst nightmare.

Inform the Driver immediately.

The Driver wastes no time following our advice and recruiting an accountability partner, a reliable one, who agrees to meet him every day at 5pm.

Right now it’s 4:59pm. The Driver pulls over to the side of the road. Right behind him is his partner, in his own car, who pulls over right alongside him.

Together the two perform their implementation intentions together. And like magic, an hour later, they both find themselves unflinchingly executing their growth activities.

Starting The Grit Protocol turns out to have been an enormously consequential decision. Now, the Passenger, as much he would like to, has great difficulty sabotaging them, and as a result, as the weeks and months go by, the Driver ends up attending almost every one.

Soon his implementation intentions have become an unshakable habit, and consequently so has going to the library and writing his book.

In six months, his book is complete.

Now that we’ve so effectively helped the Driver overcome his procrastination so that he can consistently execute his growth activities, we should, at last, take our own advice.

And now that we understand The Grit Protocol’s underlying principles, let’s unpack exactly how to conduct each TGP meeting.

How to conduct The Grit Protocol Daily Meetings

Remember that growth activities are defined as activities that drive your most important long-term goal. So first, before you even begin these meetings, you and your partner will need to have decided on, for now, one long-term goal that you’re each committed to achieving over the next 6–12 months. Just one. Trust me. Once you’ve decided on one goal, go ahead and write it down.

Now, every weekday, Monday through Friday, you and your partner will meet over the phone at a regularly scheduled time. During these brief, 15–20 minute meetings, you’ll take turns executing the following steps:

Step One: Review your long-term goals

During this first part of the meeting, your partner will ask you to read your goal out loud. Verbatim. Just like you’re reciting the pledge of allegiance. This quick ritual will remind you, no matter how currently mired you are in urgent maintenance tasks, what’s truly important.

Step Two: Decide on your growth activities for the following day

Next your partner will ask you what next actions you could take on to move your long-term goal forward? You’ll list them and decide on the ones you’ll realistically be able to perform over the next 24 hours. The result is a list of tomorrow’s tasks.

Step Three: Implementation Intentions

For each one of the next tasks you’ve committed to, your partner will ask you when and where specifically will you complete them?

Step Four: Switch

Now it’s your turn to lead your partner through these steps.

How to Master The Grit Protocol

In this article I’ve laid out the basics of TGP, but there’s far more to this partner-based productivity system than I’ve had time to write about here.

That’s why if you’re serious about conquering the Passenger and making daily unshakable progress towards your long-term goals, you should sign up for the Get Gritty Mini-Course, a free 6-part video series that will teach more about this powerful system.

Conclusion

While it’s temping to think so, the key to productivity is not getting more things done. It’s getting more of the right things done. In other words executing the specific tasks that drive our most important long-term goals. Growth activities.

Unfortunately, if we want to consistently execute growth activities, we have to outsmart the live for today part of our brain, the immediate gratification-loving Passenger, which causes us to procrastinate every time we attempt them.

But we also have to realize that while we can’t overpower the Passenger — he’s just too strong — it is possible to outmaneuver him.

The Grit Protocol is a remarkably effective method for doing just that. It is a powerful system for consistently executing the kinds of activities that don’t just help us maintain our personal status quo, but help us move well beyond it.

A bit unconventional, I’ll admit. Largely, because we’re so used to thinking of productivity as something we do alone. But we desperately need to change that. Because as it turns out, the most powerful asset we have for beating the Passenger and executing our growth activities, is each other.

Acknowledgements:

Thank you to Kent Berridge, Tim Pychyl, Frank Wieber, and Hadas Okon-Singer for allowing me to interview them for this piece. Your contributions were invaluable.

Thank you to Steven Pressfield’s War of Art for the inspiration. And Piers Steel’s wonderful book The Procrastination Equation as well as Joseph Ledoux’s Anxiety, which both helped inform my thinking on the topic.